It’s the night after our first ‘More-Than-Human Participatory Research Workshop’. I am sitting in a friend’s living room, explaining the last 48 hours or so.

‘I have been at a workshop at the Open University, led by the Animal-Computer Interaction Team’, I say.

‘We were working with dogs’, I say.

‘Trying to work out how we might work with dogs’, I say.

‘How we might work with dogs as research participants, rather than simply objects of research’, I say.

In spite of my gentle approach, there’s a momentary pause, quizzical looks shared across the dinner table.

‘But they can’t be participants, can they, as they haven’t got a choice about being in the workshop?’, responds my friend.

‘It’s true’, I reply, ‘mediating the dogs’ participation were the dogs’ handlers, and indeed, early in the workshop, when we were all introducing ourselves, another participant, a cultural geographer, Owain, did ask why the dogs weren’t in the room with us, there and then, introducing themselves, getting to know us. And Helen, one of the dog handlers, replied that she was checking the space out for the dogs before bringing them in, and checking us out too.’

More quizzical – or might those be sceptical? – looks around the dinner table. More sipping of wine.

I try again. ‘As another of the workshop participants, Niamh, said – and I am paraphrasing here – participation should not be presumed to be about equal participation [that’s a fallacy, because power is a dynamic flow – though I didn’t go into this over the dinner table] but about appropriate participation, meaningful participation.’

A few nods now.

Emboldened, I continue, ‘So working with dogs as participatory subjects is about taking the dog’s presence, behaviour, responses, actions, activities seriously – it’s about recognising the potential for contribution through recognising the potential for contribution.’

‘And that can reflect back on how we currently work with humans in research too’, replies C.

Bingo. Yes. (In thinking about dogs as participants, we push against some of the assumptions implicit to Human-Computer Interaction.)

But it’s not just that.

Or it’s more than that.

***

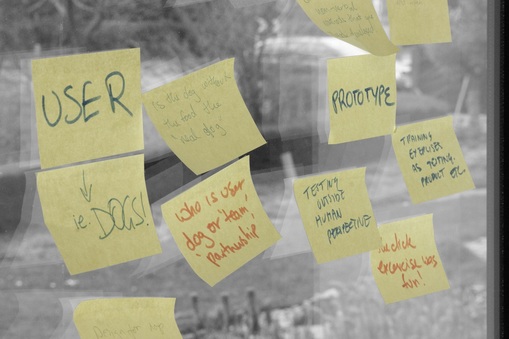

We focus on the buttons that release doors. We reflect on how the dogs – Winnie and Cosmo – had to press their paw to the centre of the mock button before being rewarded (with clicker, treat and positive affirmation ‘Good Boy!’). And how difficult this task is because it demands precision (paws hit the edge, slip off, miss the centre). And this leads us to recognise that the button design unnecessarily focuses attention on a hot spot (Owain has recently downloaded an app to his phone – the Big Red Button app – which demonstrates the button-centre concept perfectly). The button is a bull’s eye, the dead centre, the apocalypse, lift off, jackpot. The button is a cultural repository. But it’s also an unnecessary restriction and challenge.

So, imagine the button is replaced by a long, vertical strip. There is no dead centre, no requirement for precision, for a steady and accurate finger or paw. This strip, an extended contact zone, extends the potential for connection between one thing and another.

This is our proposed new design but we decide to put functionality aside for now and focus on pleasure. What would a dog like from a strip such as this (textures? smells? activities? challenges?)? What might make the task of contact one of pleasure, engagement, stimulation – beyond the reward of achievement itself (Good Boy!)? We will start with the dogs’ experiences, rather than being led by the necessity of functionality, flipping the instrumental and the aesthetic. And for this, we will need to engage in some deep hanging about with dogs.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed