I think the first and basic thing is that the dogs did come into the room, were there for quite a long time and were active. This at least opened up the process to their interventions and agencies. Clearly the handlers were critical mediators between us and the dogs but that is fine. We can’t expect to learn new languages or be comfortable with strangers instantly. All the way through this project and in the wider area of more-than human politics, ethics etc., it makes sense to draw upon those who are ‘expert’ and empathetic in relation to non-humans of one kind or another.

The differing behaviours of the dogs as individuals and how they interacted with each other and with the humans present was important to me. [Dogs for the Disabled brought three dogs, two working dogs and one of their own pet dogs – Ed.]. Clearly the dog handlers had their agendas in terms of what they want, need and expect the dogs to do. In terms of participatory research with dogs to respond to particular design needs it would be important to consider the specificities of particular dogs in particular relationships in particular settings. A sort of qualitative ethology of human, non-human, material assemblages.

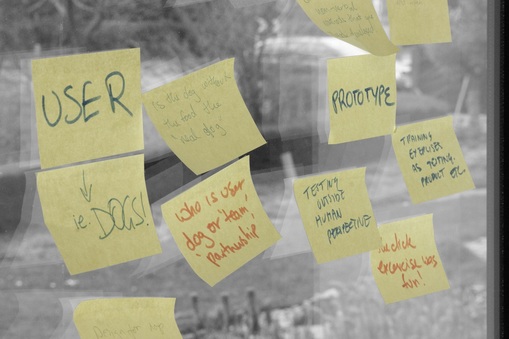

Regarding the clicker exercises we did [see overview here – Ed.], I thought it was sort of interesting doing the clicking but not that interesting being the dog. This was done on the premise (I think) of showing how sharp the dogs are. But I think anyone who watches, and takes various kinds of animals seriously will know they have plenty of abilities / skills / capacities which some sometimes (often) exceed human capacities. We must avoid any cheap notions of becoming-animal, it is not respectful of their otherness, of their ways of being in the world. Speaking of that, the workshops were quite visually orientated, less was made of smell and sound. Of course we can’t get our senses to do what they do but maybe we should have taken a bit of time to watch them smelling and to watch them listening. (If you got a cat – when it is alert – watch its ears as they twitch around focusing on one sound then another). As I said at the time I liked the first session when Winnie was just in the room more or less doing her own thing. And also when Winnie and Cosmo were switching back and forth between the training exercises and doing doggy playing. Haraway (1992) states that ‘biology and evolutionary theory over the last two centuries have…reduced the line between humans and animals to a faint trace’ (193). So because of that – although otherness has to be respected – I don’t think it rocket science to look carefully at animals and get some sense of their intentions, well-being or otherwise – probably true for trees and bees too. I don’t see anthropomorphism as the big impediment to thinking animals and non-humans as other do. There are many shared traits between us. Winnie did a big yawn at one point. For me there are clear continuities between yawning dog and yawning human in terms of affective state.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed