I was struck by the following:

On one hand the intimacy of the relationship between the keepers and the bees insofar as the frame system lets the keepers, in effect, see into the working of the colony, even to the extent of seeing into the cells, seeing the queen in action, etc.; and on the other the otherness, the alieness, that exists between ‘becoming bee’ and ‘becoming human’.

The frame system seems very important to me insofar at it serves the above purposes for the keepers, e.g. monitoring hive health, but it also serves the bees well (as far as one can tell) quite simply as a place to make home. The technologies and practices of bee keeping have been shaped by bee agency over time insofar as it is a process of material, technological and habitual relational feedback/evolution. This process can perhaps be reflexively and technically refined and accelerated in ‘collaborative’ work with bees. The notions of various forms of biosensors to gather colony feedback offers some potential here.

I was struck by the attention to material and spatial detail - the size of the opening into the hive, which way the hives face in relation to each other. Also by the sensitivity to bee practice (such as slow moments, not standing in the flight path), and the notion of bee welfare not only for instrumental reasons but also for ethical reasons. The extraordinary socio-spatial habits of the colonies in terms of sex, learning and swarming show a rich forum of geographical becoming (as all animals do).

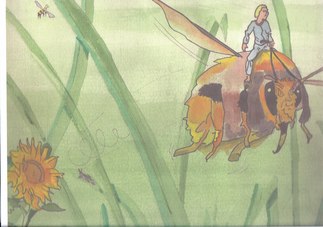

Dogs can clearly develop close emotional bonds with humans, and two-way communication. Through touch, sound, smell, and other senses, co-practice is commonplace and well developed. (The shared mammalness of both, the co-evolution of both are just two reasons for this). The intimacy between bees and humans (if it does exist) is of a different order, but in some respects at least, is no less significant.

The notion of beekeeping as more of a highly contested art, with perpetual openness for continued learning, than a settled and agreed practice, speaks to the great complexity of not only bees as a species, but also bees as embedded in ecology, and bees as embedded in the social and the adapted landscapes of modernity.

The issue of the super-organism and individual is a real challenge to thinking about human bee relationships as it is to other swarm, heard and flock animals. The Cartesian settlement of the human individual makes this challenging. Individual bees transmogrify from one part/function of the super-organism to another as they ‘grow up’.

If humans and bees are seen as agents in the (ecological) meshworks (Ingold) of life then we are already bound into conversations, perhaps, exchanges for sure, which have profound impacts on the flourishing (or otherwise), of both and of the meshwork itself.

In essence I think if we are to conduct conversations with bees we need the intermediaries of the experienced, empathetic, and open minded bee keepers. They are the ‘spokespersons’ that Latour feels are needed in the ‘parliament of things’. But they are not ‘representing fixed positions or facts, but conjectures and possibilities', and as Dobson (2010), observes, such a redefined ecological form of politics (and science) requires the development of new ways of listening, as well as new channels of speaking.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed